Canary Media (Maria Gallucci) – Steelmakers Cleveland-Cliffs and SSAB could get up to $500M each to build novel facilities that can make iron for steelmaking using hydrogen.

The Biden administration’s latest initiative to clean up heavy industries could usher in a new era for one of the dirtiest sectors of all: iron and steel.

On Monday, the U.S. Department of Energy announced up to $6 billion for commercial-scale projects that aim to demonstrate technologies for slashing greenhouse gas emissions at an array of U.S. factories. Two of the winners — the steelmakers Cleveland-Cliffs and SSAB — were each selected to receive up to $500 million for “green steel” projects that could transform how America turns iron ore into the ubiquitous high-strength metal.

Both companies are proposing to build low-emissions ironmaking facilities that run on clean hydrogen instead of coal or fossil gas. No such facilities exist yet in the United States, and only one worldwide is operating at a meaningful scale today: the Hybrit project in Sweden, in which SSAB is a partner. Before this week’s announcement, the only other hydrogen-focused projects in the works were based in Europe and China.

“Until a few days ago, it was feeling like the U.S. was really behind, and that we needed to be making some leadership investments in our first green steel plants,” Hilary Lewis, steel director at the advocacy group Industrious Labs, told Canary Media. “And that’s what we got today.”

Cleveland-Cliffs plans to install a “hydrogen-ready” ironmaking plant at an existing complex in Middletown, Ohio. SSAB would build a new facility in Perry County, Mississippi that exclusively uses hydrogen to turn raw ore into iron.

The manufacturers will each have to contribute their own sizable share of funding, and both projects are still subject to award negotiations. But green-steel proponents say government support is crucial to getting these first-of-a-kind facilities financed, given that banks and investors are generally reluctant to back potentially risky, capital-intensive projects.

Still, building less-polluting infrastructure is only the first step. In order to drive deep emissions cuts, companies using this ironmaking technique will also have to procure large quantities of “clean hydrogen” in particular — very little of which is available right now. Today, the vast majority of hydrogen is produced using fossil gas in an emissions-intensive process. The lowest-carbon alternative is to make hydrogen with water and huge amounts of renewable electricity; this is also called “green hydrogen.”

In that way, the quest for greener steel is bound up in the success of two broader efforts taking shape across the United States: dramatically boosting the production of clean hydrogen and drastically scaling up the nation’s clean energy capacity.

Striving toward cleaner steel

Globally, steel production generates as much as 9 percent of human-caused CO2 emissions every year — more than any other heavy industry.

Part of the reason is simply that manufacturers make so much of it: nearly 2 billion metric tons per year worldwide. The essential alloy forms the hulls of cargo ships and parts of airplanes. It’s found in buildings, bridges and roads, and it’s used in vehicles, appliances and cookware.

In recent years, the U.S. steel industry has made strides to curb its carbon footprint by increasing the amount of recycled steel used in end products, and then melting all of that scrap metal in electric-powered arc furnaces. Today, about 70 percent of America’s steel is made this way, while roughly 30 percent is produced in traditional coal-hungry mills. (Worldwide, the story plays out in reverse.)

But while recycled steel can satisfy some of the nation’s demand for the sturdy metal, it doesn’t fully replace the need for “primary” steel, which is essential for the high-strength components in vehicles. It also doesn’t diminish the need to clean up or replace the dirty facilities that still exist.

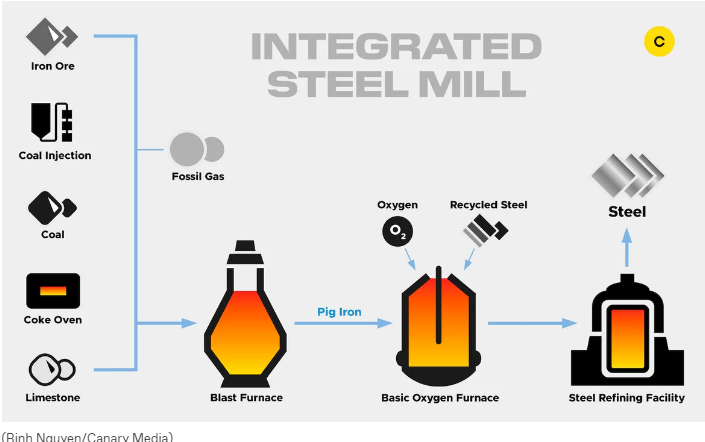

Right now, most primary steel is made using a blast furnace — by far the biggest emissions culprit — in what are known as integrated steel mills.

In blast furnaces, iron ore and purified coal (or “coke”) are dumped into a vessel, along with a sprinkling of processed limestone. A blast of hot air reaching up to around 2,800°F is blown into the furnace at high speeds, driving chemical reactions. Carbon monoxide bonds with oxygen atoms in the iron ore, forming CO2 that’s released into the air. The resulting iron flows out of the furnace like lava; from there, it moves into a basic oxygen furnace to become finished steel.

The United States still operates 13 aging blast furnaces, seven of which are owned by Ohio-based Cleveland-Cliffs.

This week, the manufacturer said it plans to replace one of those blast furnaces in Middletown, Ohio with a “direct reduced iron” plant that can run on hydrogen. Cleveland-Cliffs anticipates it will spend around $1.3 billion itself over a five-year period for the project, which could be completed by 2029.

The direct reduced iron (DRI) process involves dropping iron-ore pellets into a shaft furnace. The combination of hydrogen gas and heat causes the oxygen atoms in iron ore to combine with hydrogen and form water. DRI plants can be paired with electric arc furnaces to turn iron into finished steel using only electricity. But in the case of Cleveland-Cliffs, the company is building two electricity-powered melting furnaces that will feed the iron into its existing basic oxygen furnace.

The investments are expected to slash emissions at the Ohio facility by 1 million metric tons of greenhouse gases every year, according to the DOE.

“Hydrogen is the real game-changing event in ironmaking and steelmaking, and that’s our Cleveland-Cliffs pathway to the production of green steel,” Lourenco Goncalves, the company’s CEO and chairman, said on a January 30 earnings call.

DRI technology is decades old, and nearly 100 such facilities have been deployed worldwide to date — including three in the United States. But all of them use fossil fuels in the shaft furnace. Rather than using hydrogen directly, these facilities take fossil gas or coke-oven gas to produce a “reducing gas,” containing hydrogen and carbon monoxide, that removes the oxygen content from iron ore.

Cleveland-Cliffs said its new DRI facility in Middletown will have the “flexibility” to be fueled by fossil gas, which would reduce the carbon-intensity from ironmaking by more than half. The plant can also run on a mix of gas and clean hydrogen, or on clean hydrogen alone. The latter option would reduce the carbon-intensity of making iron by over 90 percent.

Meanwhile, the other big winner this week, SSAB, said it’s planning to skip gas altogether and go straight to using clean hydrogen in Mississippi.

The Swedish manufacturer was selected to build the world’s first commercial-scale facility using Hybrit technology, though it didn’t say by when. The existing Hybrit pilot plant in Sweden uses hydrogen to produce direct reduced iron. But unlike other DRI facilities, Hybrit has a proprietary design — one its developers say is optimized to run on only hydrogen, instead of fossil gas or a mix of fuels.

SSAB is also considering expanding its existing steelmaking facility in Montpelier, Iowa to make use of new clean iron supplies from its Mississippi plant. As part of the initiative, SSAB said it signed a letter of intent for Hy Stor Energy to supply green hydrogen and renewable energy in Mississippi. Hy Stor is developing a hydrogen “hub” in that state, where it plans to use on-site, off-grid renewable energy projects to produce hydrogen, which is then stored in underground salt caverns to deliver energy on-demand and around the clock.

Hilary Lewis said that, in light of this week’s news, “Green hydrogen developers should have their ears perked up and be reaching out to make sure that their projects are the ones supported by this huge new demand.”

Industrious Labs and other green-steel proponents will “be working on that as well, to make sure that they get the cleanest possible hydrogen for those facilities,” she added.